Aga Khan Award 2016

30 November 2016

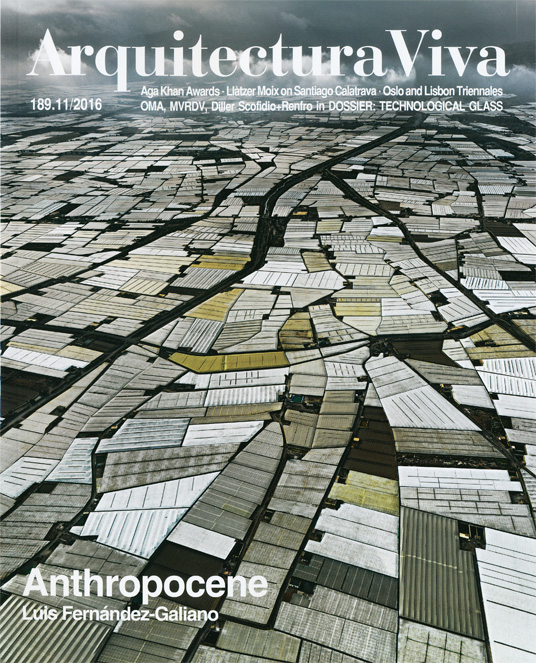

Elogio del pluralismo

Aga Khan Award 2016

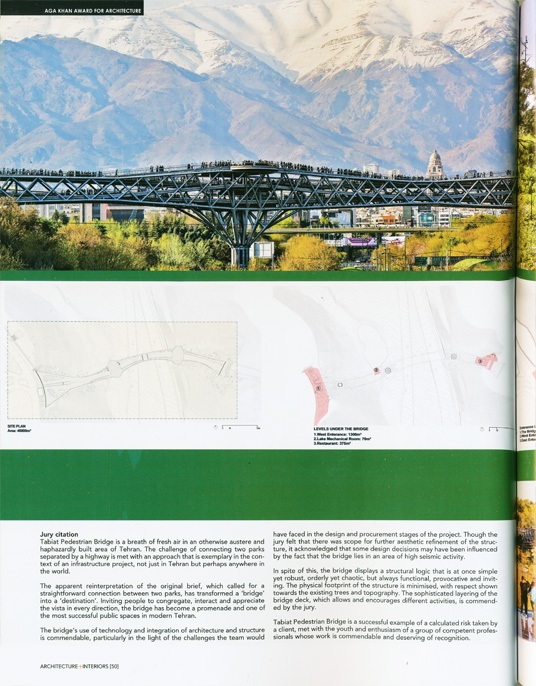

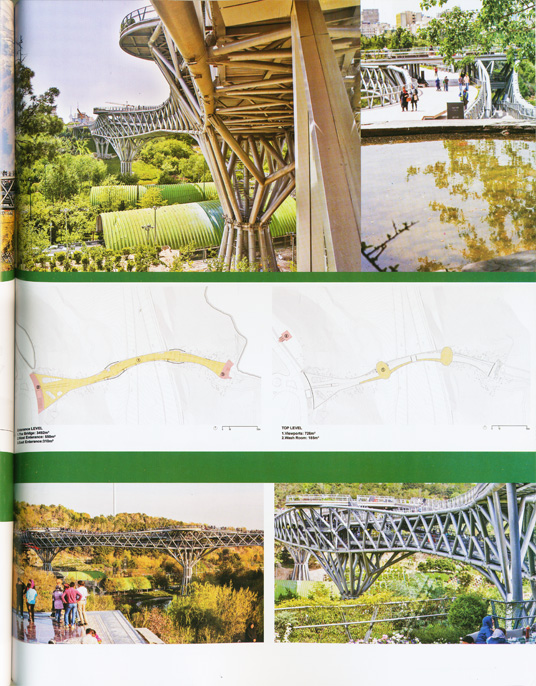

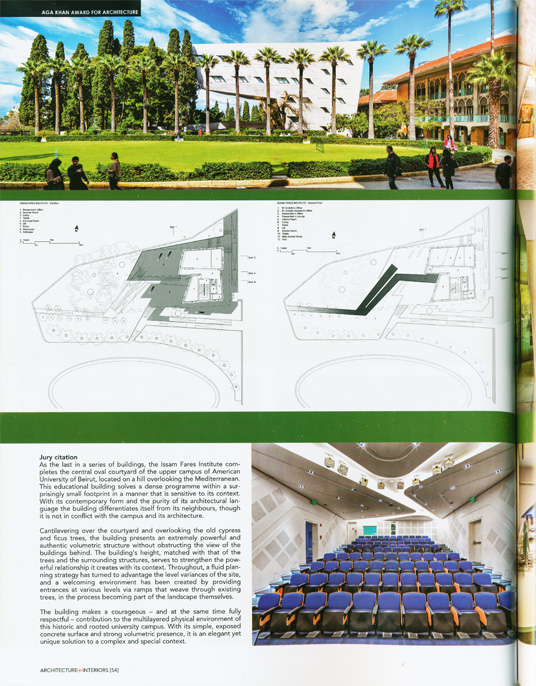

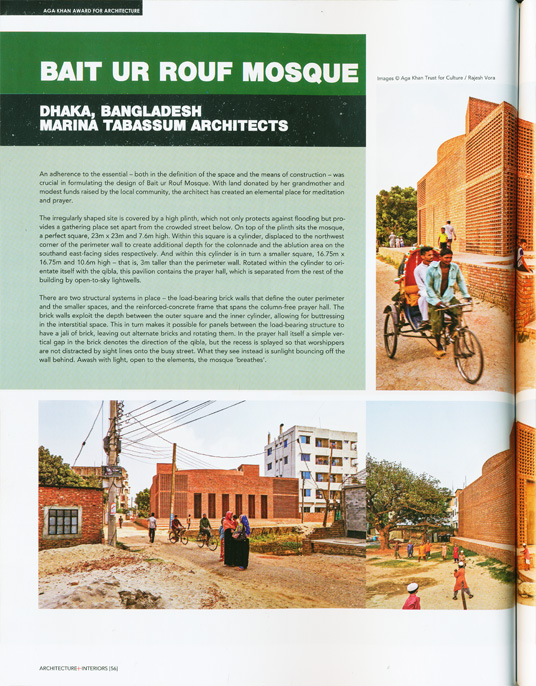

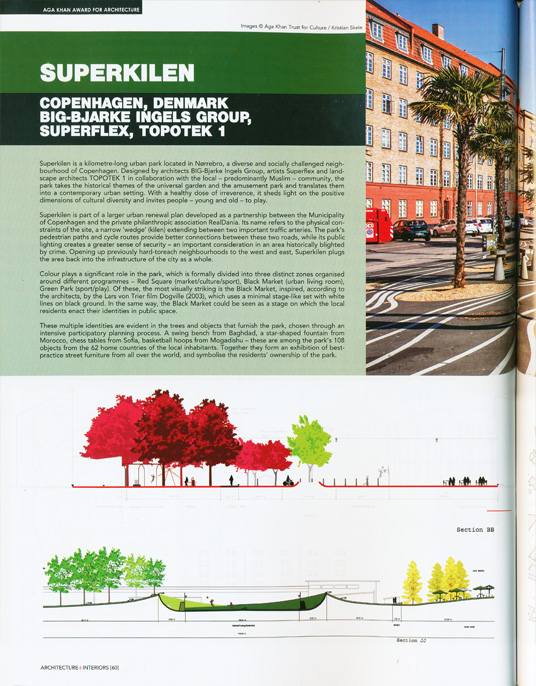

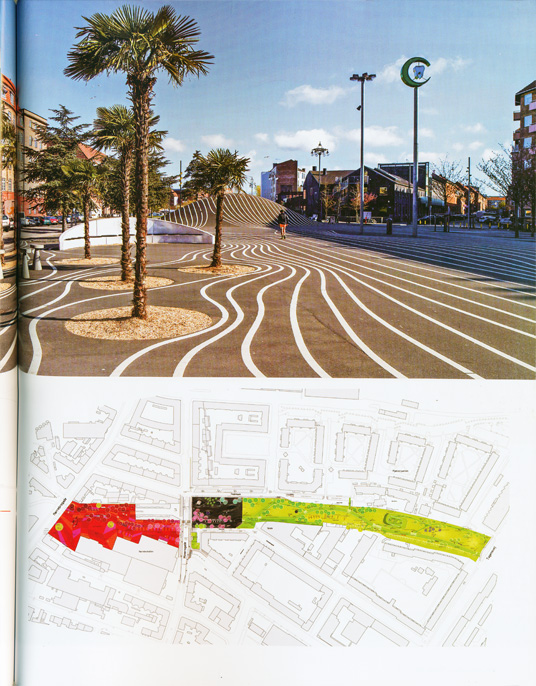

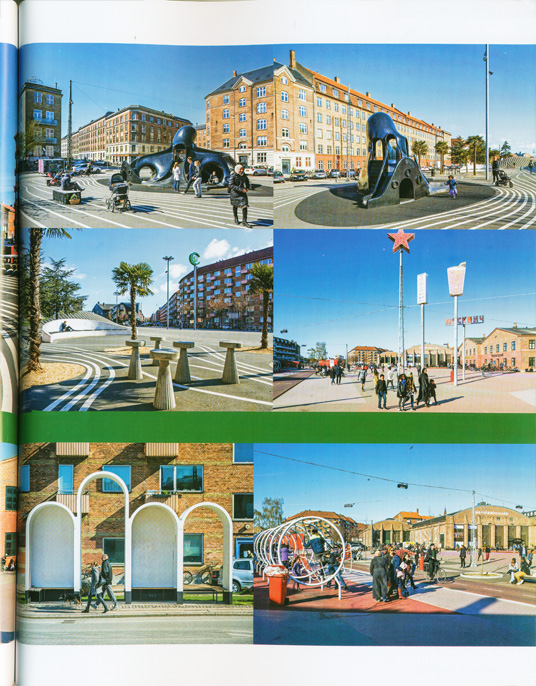

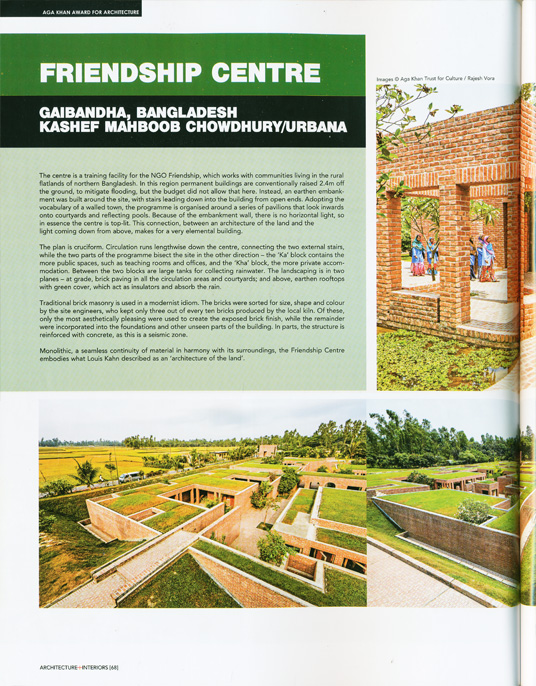

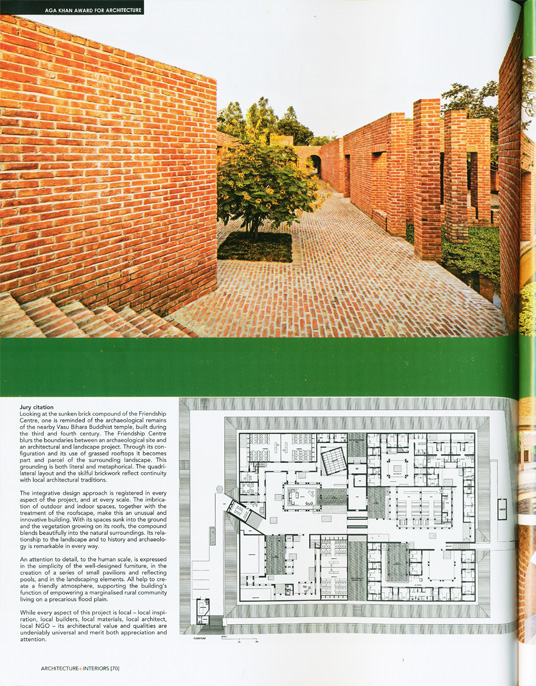

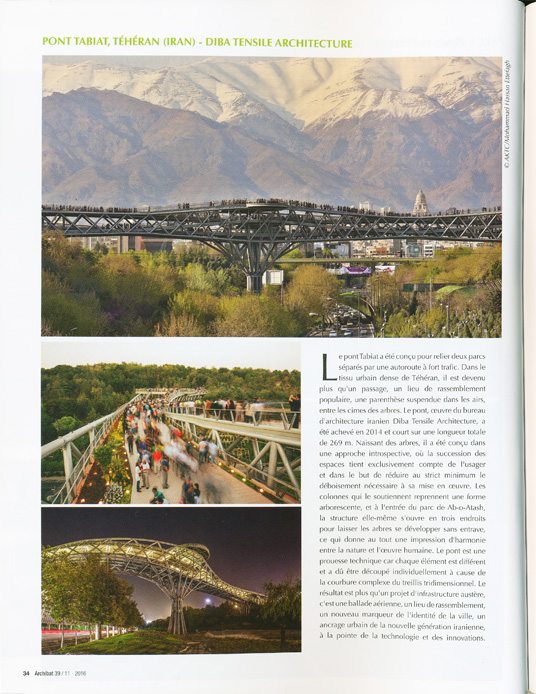

Establecido en 1977 y otorgado por el Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), que dirige el español Luis Monreal, el Premio Aga Khan de Arquitectura se ha ido consolidando a lo largo de los años hasta convertirse en una referencia no sólo de las arquitecturas del mundo islámico, sino también de los edificios de calidad realizados con recursos locales y atentos al contexto. Dirigido por Farrokh Derakhshani, el premio trienal, dotado con un millón de dólares, y cuyo jurado presidió en esta edición Luis Fernández-Galiano, ha recaído en seis obras de diferente condición y ubicaciones muy distintas, cuya característica común es el modo en que contribuyen a mejorar su entorno: la mezquita Bait Ur Rouf en Daca (Bangladés), de Marina Tabassum; el centro comunitario en Gaibandha, también en Bangladés, de URBANA / Kashed Mahboob Chowdhury (imagen superior); la biblioteca y el centro de arte infantil en un hutong pequinés, de ZAO/ standardarchitecture y Zhang Ke (véase Arquitectura Viva 180); el puente peatonal Tabiat en Teherán (Irán), de Diba Tensile Architecture / Leila Araghian y Alireza Behzadi; el Instituto Issam Fares en Beirut (Líbano), de Zaha Hadid Architects; y, flnalmente, el Parque Superkilen en Copenhague (Dinamarca) de BIG / Bjarke Ingels Group. Topotek 1 y Superflex (véase AV Monografjas 162), un singular proyecto que supone un elogio del pluralismo y de la tolerancia en el contexto de una Europa acosada de nuevo por el fantasma del nacionalismo y la xenofobia.

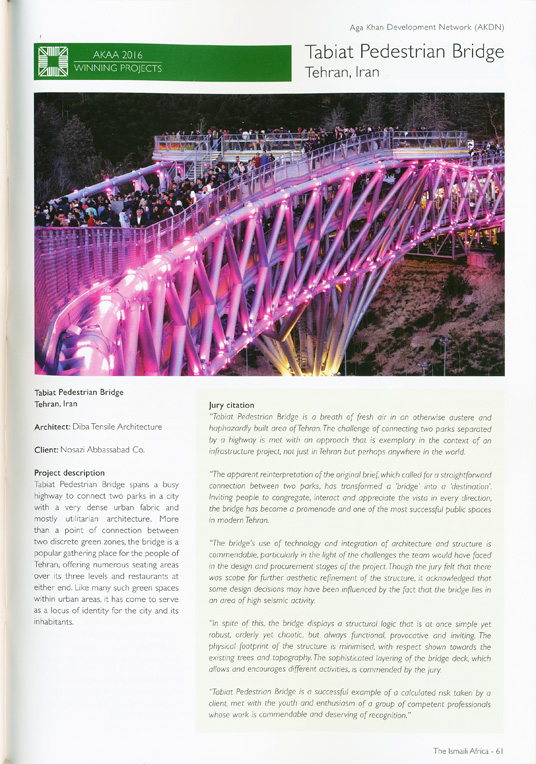

Instituted in the year 1977 and given by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), which the Spaniard Luis Monreal heads, the Aga Khan Award for Architecture has consolidated through the decades and become a benchmark not only for contemporary architecture in the entire Islamic world, but also for quality buildings made with local resources and addressing grassroots contexts. Headed by Farrokh Derakhshani, the triennial award - which comes with a US$1 million award and whose jury has in this cycle been presided by Luis Fernández-Galiano - has fallen upon six works that differ much in nature and location, but which share a clear desire and effort to contribute to improving the environments and societies that they are in. They are: the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in Dhaka (Bangladesh), by Marina Tabassum; the Friendship Center, a community facility in Gaibandha (Bangladesh), by URBANA / Kashed Mahboob Chowdhury (image above); a children's library and art center for a hutong in Beijing (China), by ZAO / standardarchitecture and Zhang Ke (see Arquitectura Viva 180); the Tabiat Pedestrian Bridge in Tehran (Iran), by Diba Tensile Architecture / Leila Araghian and Alireza Behzadi; the Issam Fares Institute in Beirut (Lebanon), by Zaha Hadid Architects; and finally the Superkilen park in Copenhagen (Denmark), by BIG / Bjarke Ingels Group, Topotek 1, and Superflex (see AV Monographs 162) a unique project that is a eulogy to pluralism and tolerance in a European continent once again under assault from the phantoms of nationalism and xenophobia.

Centre d'art et bibliothèque pour enfants micro yuan'er, pékin (chine)

ZAO/standardarchitecture

L'architecture traditionnelle chinoise des hutongs (ruelles en chinois) disparait de plus en plus rapidement pour laisser place, à Pékin comme clans nombre d'autres villes chinoises, àune architecture contemporaine aux standards internationaux. Les courettes ancestrales, leurs toitures inclinées et le réseau complexe de ruelles sont certes visibles dans certains quartiers de Pékin, mais ce ne sont malheureusement que des espaces servant de témoin d'un passé révolu, des musées à ciel ouvert sur ce qu'était la Chine. C'est le cas d'ailleurs pour les tissus architecturaux traditionnels dans plusieurs pays dans le monde, l'enjeu est de faire vivre ces espaces dans le monde actuel. ZAO / standardarchitecture a réussi le pari de s'implanter dans un quartier encore préservé, pour y proposer des espaces communautaires pour leg habitants du quartier : une bibliothèque pour les enfants et un centre d'art pour les adultes et les personnes âgées. Le programme est simple, mais l'intégration à l'environnement s'est révélée d'une extrême sensibilité. Les architectes ont dans leur projet rèutilisé les petites constructions qui encombraient la cour intérieure. D'autres éléments ont été rajoutés, cette foisci en les faisant reposer sur une fondation flottante de poutres d'acier creuses posées à mème le sol afin de protéger les racines d'un grand arbre pagode six fois centenaire. Les matériaux utilisés ont aussi été choisis dans la palette déjà présente dans le hutong, à savoir briques grises, bois et verre. La bibliothèque, destinée aux enfants est elle un ingénieux travail d'adaptation. Tout d'abord adaptation aux utilisateurs, puisque l'aménagement intérieur et les meubles se veulent ludiques ; ensuite une adaptation au site, puisque les architectes ont mis au point une innovation esthétique afin de coller à l'environnement, les murs de la bibliothèques sont en béton mâtiné à l'encre de chine.

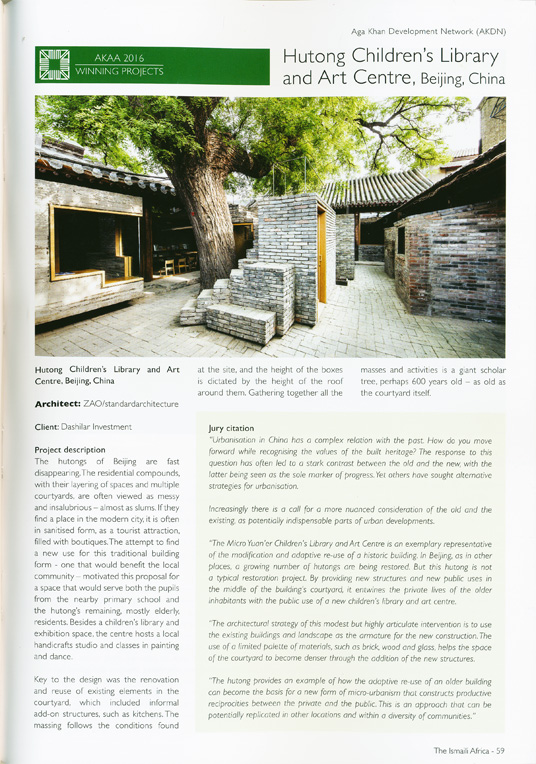

Hutong Children's Library and Art Centre

Beijing, China

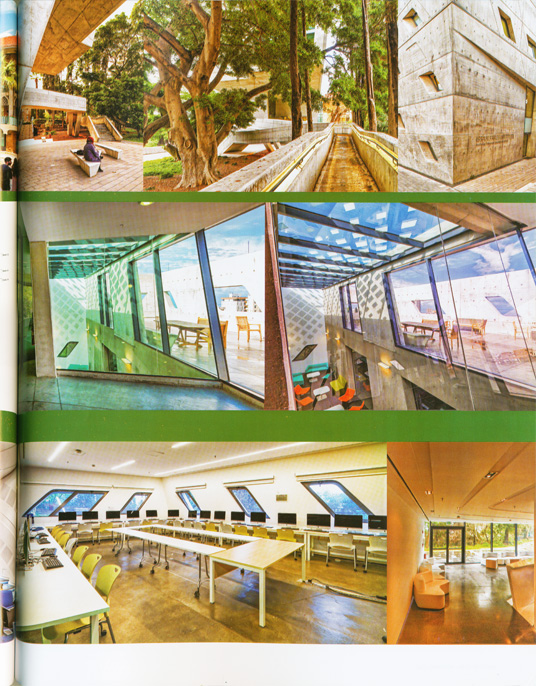

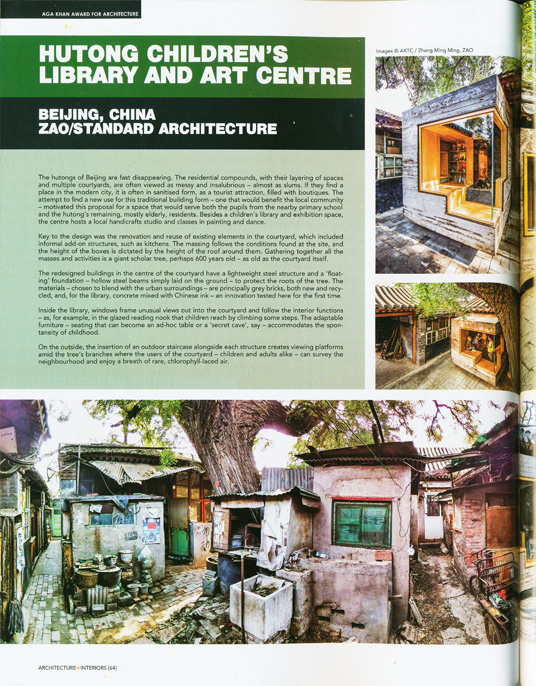

The hutongs of Beijing are fast disappearing. The residential compounds, with their layering of spaces and multiple courtyards, are often viewed as messy and insalubrious – almost as slums. If they find a place in the modern city, it is often in sanitised form, as a tourist attraction, filled with boutiques. The attempt to find a new use for this traditional building form – one that would benefit the local community – motivated this proposal for a space that would serve both the pupils from the nearby primary school and the hutong's remaining, mostly elderly, residents. Besides a children's library and exhibition space, the centre hosts a local handicrafts studio and classes in painting and dance.

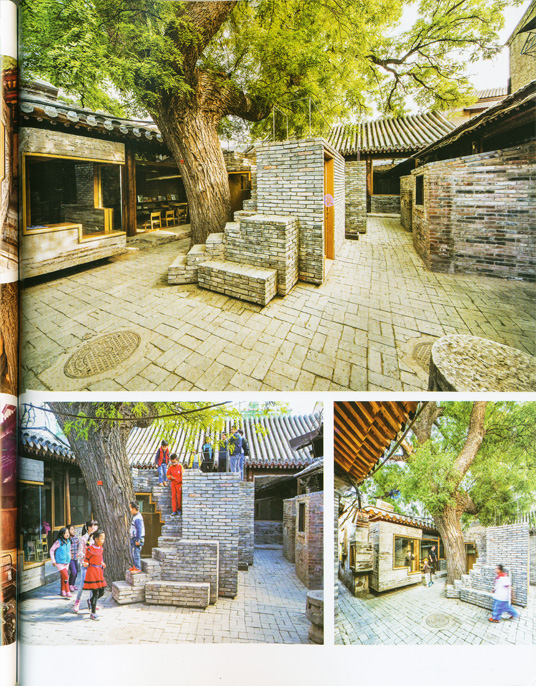

Key to the design was the renovation and reuse of existing elements in the courtyard, which included informal add-on structures, such as kitchens. The massing follows the conditions found at the site, and the height of the boxes is dictated by the height of the roof around them. Gathering together all the masses and activities is a giant scholar tree, perhaps 600 years old – as old as the courtyard itself.

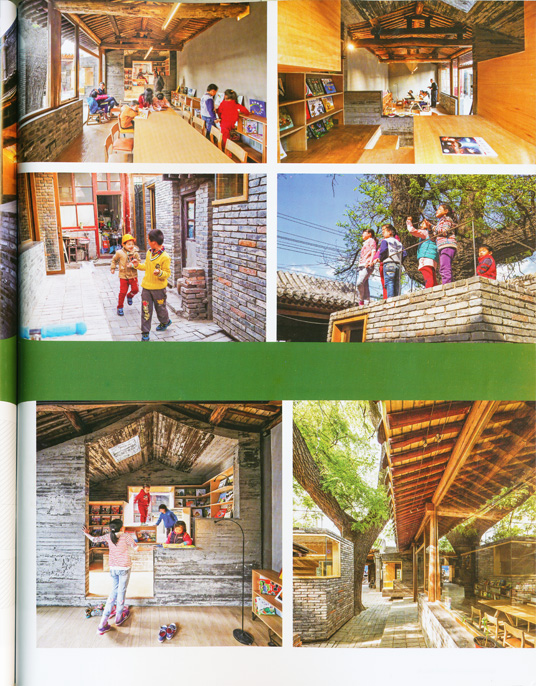

The redesigned buildings in the centre of the courtyard have a lightweight steel structure and a 'floating' foundation – hollow steel beams simply laid on the ground – to protect the roots of the tree. The materials – chosen to blend with the urban surroundings – are principally grey bricks, both new and recycled, and, for the library, concrete mixed with Chinese ink – an innovation tested here for the first time.

Inside the library, windows frame unusual views out into the courtyard and follow the interior functions – as, for example, in the glazed reading nook that children reach by climbing some steps. The adaptable furniture – seating that can become an adhoc table or a 'secret cave', say – accommodates the spontaneity of childhood.

On the outside, the insertion of an outdoor staircase alongside each structure creates viewing platforms amid the tree's branches where the users of the courtyard – children and adults alike – can survey the neighbourhood and enjoy a breath of rare, chlorophyll-laced air.

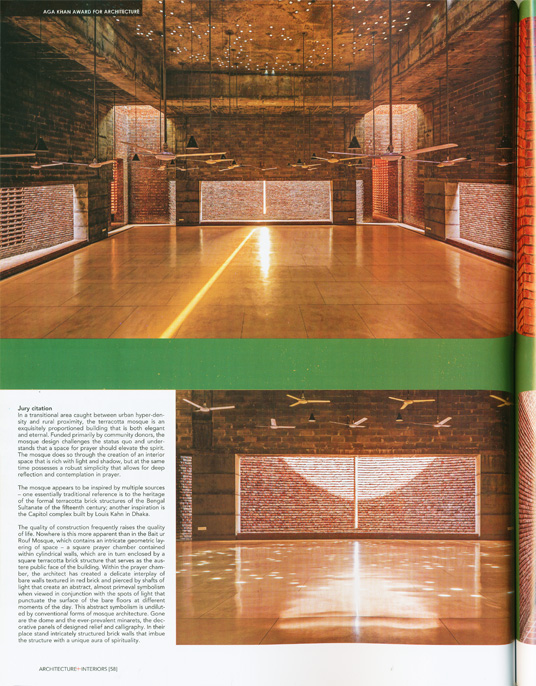

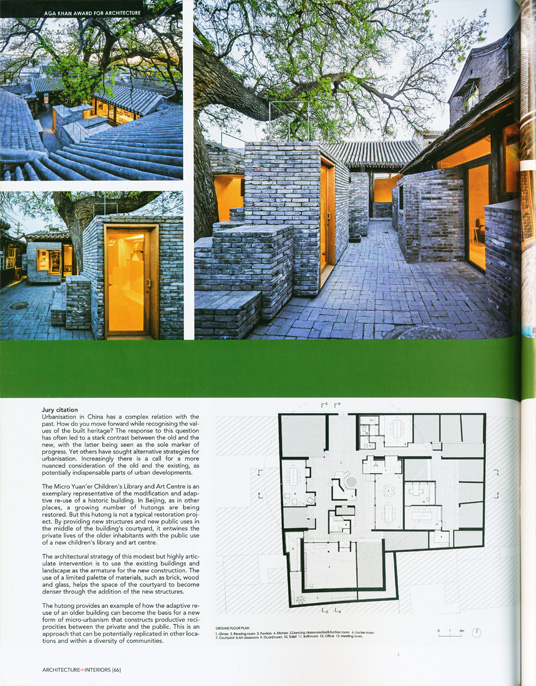

Jury Citation

"Urbanisation in China has a complex relation with the past. How do you move forward while recognising the values of the built heritage? The response to this question has often led to a stark contrast between the old and the new, with the latter being seen as the sole marker of progress. Yet others have sought alternative strategies for urbanisation. Increasingly there is a call for a more nuanced consideration of the old and the existing, as potentially indispensable parts of urban developments.

"The Micro Yuan'er Children's Library and Art Centre is an exemplary representative of the modification and adaptive re-use of a historic building. In Beijing, as in other places, a growing number of hutongs are being restored. But this hutong is not a typical restoration project. By providing new structures and new public uses in the middle of the building's courtyard, it entwines the private lives of the older inhabitants with the public use of a new children's library and art centre.

"The architectural strategy of this modest but highly articulate intervention is to use the existing buildings and landscape as the armature for the new construction. The use of a limited palette of materials, such as brick, wood and glass, helps the space of the courtyard to become denser through the addition of the new structures.

"The hutong provides an example of how the adaptive re-use of an older building can become the basis for a new form of micro-urbanism that constructs productive reciprocities between the private and the public. This is an approach that can be potentially replicated in other locations and within a diversity of communities."

Project data

Client: Beijing Dashilar Liulichang Cultural Development Ltd.

#8 Cha'er Hutong Inhabitants: WANG Zengqi, GIAO Dazhen, MAN Weiguo, FENG Yubao, ZHANG Jiankun

Principal Architect: ZHANG Ke

Design Team: ZHANG Mingming, FANG Shujun, Ao Ikegami, HUANG Tanyu, Margret Domko, Ilaria Positano

Contractors: LIU Shanjie, WANG Changjun, WANG Zhanjun

Total Area: 145㎡

Cost: 105,000USD

Commission: September 2012

Design: September 2012 – July 2014

Construction: March 2014 – December 2015

Completion: September 2014 – December 2015