Thinking small in china

01 November 2012

ARIC CHEN

White the West frets about the “new normal,” with its paralytic combination of panicked urgency and concomitant complacency, the feeding frenzy continues in China. Zaha Hadid is building a contemporary art center in Chengdu that will be twice as big as the opera house she just completed in Guangzhou. Norman Foster is competing for another mammoth Beijing airport that would make the one he finished only four years ago look like a skid mark on the tarmac. A number of the usual suspects, including Hadid and Herzog & de Meuron, are angling for the job to design a new National Art Museum of China building in Beijing that, at 60,000 square meters (or is it 160,000-it really doesn't matter), is meant to outdo the National Stadium (aka, the Bird's Nest), which will be next door. While it is probably true that the choicest jobs are still going to Western designers, there is no shortage of work for their Chinese counterparts. Indeed, a common critique of and by young Chinese architects is that they're so busy building that they hardly have time to think. In China, research and experimentation are not so much abstract exercises as on-the-job training. But while the exigencies of contemporary China call for broad strokes-in the next twenty years, Chinese cities are expected to add more than the current population of the United States-the actual conditions are more nuanced.

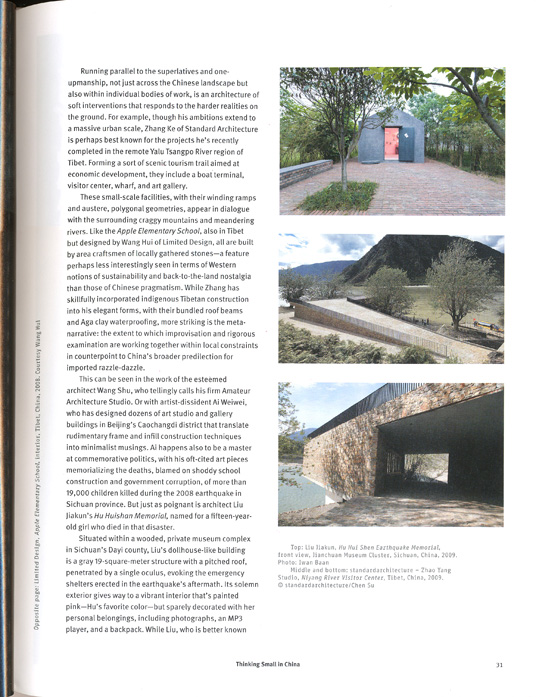

Running parallel to the superlatives and one-upmanship, not just across the Chinese landscape but also within individual bodies of work, is an architecture of soft interventions that responds to the harder realities on the ground. For example, though his ambitions extend to a massive urban scale, Zhang Ke of Standard Architecture is perhaps best known for the projects he's recently completed in the remote Yalu Tsangpo River region of Tibet. Forming a sort of scenic tourism trail aimed at economic development, they include a boat terminal, visitor center, wharf, and art gallery.

These small-scale facilities, with their winding ramps and austere, polygonal geometries, appear in dialogue with the surrounding craggy mountains and meandering rivers. Like the Apple Elementary School, also in Tibet but designed by Wang Hui of Limited Design, all are built by area craftsmen of locally gathered stones-a feature perhaps less interestingly seen in terms of Western notions of sustainability and back-to-the-land nostalgia than those of Chinese pragmatism. While Zhang has skillfully incorporated indigenous Tibetan construction into his elegant forms, with their bundled roof beams and Aga clay waterproofing, more striking is the meta-narrative: the extent to which improvisation and rigorous examination are working together within local constraints in counterpoint to China's broader predilection for imported razzle-dazzle.

This can be seen in the work of the esteemed architect Wang Shu, who tellingly calls his firm Amateur Architecture Studio. Or with artist-dissident Ai Weiwei, who has designed dozens of art studio and gallery buildings in Beijing's Caochangdi district that translate rudimentary frame and infill construction techniques into minimalist musings. Ai happens also to be a master at commemorative politics, with his oft-cited art pieces memorializing the deaths, blamed on shoddy school construction and government corruption, of more than 19,000 children killed during the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan province. But just as poignant is architect Liu Jiakun's Hu Huishan Memorial, named for a fifteen-year-old girl who died in that disaster.

Situated within a wooded, private museum complex in Sichuan's Dayi county, Liu's dollhouse-like building is a gray 19-square-meter structure with a pitched roof, penetrated by a single oculus, evoking the emergency shelters erected in the earthquake's aftermath. Its solemn exterior gives way to a vibrant interior that's painted pink-Hu's favorite color-but sparely decorated with her personal belongings, including photographs, an MP3 player, and a backpack. While Liu, who is better known for his museum buildings, claims apolitical intentions, the memorial was nevertheless closed to the public by scandal-wary local authorities. At around the same time, the Sichuan-based architect was developing his “Rebirth Bricks,” masonry blocks made of earthquake rubble mixed with wheat, as if defining a new vernacular.

In another vein, Ma Yansong and Dang Qun of MAD responded to the existing, and endangered, typology of Beijing's historic hutong alleyway districts with their Hutong Bubble proposal, first presented during the 2006 Venice Architecture Biennale. The original concept called for globule-like insertions throughout the city's historic areas that would help reinvigorate those neighborhoods while providing facilities, such as toilets, that they currently tack.

Two years ago, one of those “bubbles” appeared in a traditional courtyard house that was renovated into an office and bar for a wine distributor. Oozing from the corner of the courtyard, the alien blob houses a bathroom and stair leading up to a roof terrace, its polished-metal surface creating distorted reflections of its ancient surroundings. While MAD's projects tend toward the grandiose-for example, gigantic buildings shaped like mountains-this single Hutong Bubble, though built for an upscale client, offers a mesmerizing and compelling argument for the firm's initial, populist vision of historic districts dotted with them. In China, even small gestures sometimes demand thinking on a big scale.